Participation for sustainable, resilient, and equitable futures: Where are we heading?

By: Caitlin Hafferty (Countryside and Community Research Institute, University of Gloucestershire), Bruna Montuori (School of Architecture, Royal College of Art, London), Dr Susanne Börner* (School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham & School of Public Health, Universidade de Sao Paulo), Kahina Meziant (Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences, Northumbria University), Fred Dunwoodie Stirton (Countryside and Community Research Institute, University of Gloucestershire), Dr Thea Wingfield (Department of Geography and Planning, University of Liverpool).

Participatory and deliberative approaches, methods, tools, and principles are becoming increasingly popular. These approaches can be broadly understood as a process by which communities and other key stakeholders can become involved in research and other decision-making processes. Participation has been widely used in academic, policy, and practice arenas for tackling complex global issues such as climate change, health, food security, and social justice.

Although there are numerous benefits for participation, there are challenges which we must navigate to help promote fair and sustainable outcomes.

To explore these issues, the Participatory Geographies Research Group (PYGYRG) of the RGS-IBG (a collective who value, practice, and promote participation) held an online event to discuss issues, opportunities, and adaptations for participation in recent times.

Below are three key themes from these debates, which we feel reflect some key considerations for the future of participation.

Participatory and deliberative democracy is critical for combatting global challenges

Over the past few decades, significant advances have been made in participatory and deliberative democracy for combatting complex global issues. Dr Thea Wingfield and Fred Dunwoodie Stirton reflected on these issues at the science-policy interface and for democratic political systems.

With a worrying trend of disconnect and distrust with politicians, policy makers, and the democratic system itself, participatory methods have been used as a tool to reshape the relationship between the governed and those who govern. Supporters cite increased empowerment of citizens and accountability of those enacting policies. Through bringing new ideas from sites of deliberation, it is hoped this participatory form of politics can be employed in key areas of contestation and conflict such as climate change and bioethics, where current systems or actors are seen to lack legitimacy and credibility.

Ultimately, participation in public decision-making can help to strengthen democracy, deliver better policies (based on better quality information), and build trust for institutions.

While participatory mechanisms are yet to be tested on a large scale, there is a swell of interest and innovation, especially at the local level. Participation is far from a one-size-fits all solution; the use of appropriate tools and mechanisms are vital to ensure legitimacy, transparency, and ultimately effectiveness. Poorly designed systems can increase distrust, or reproduce existing inequalities.

We need to consider the practical and ethical issues of digital participation

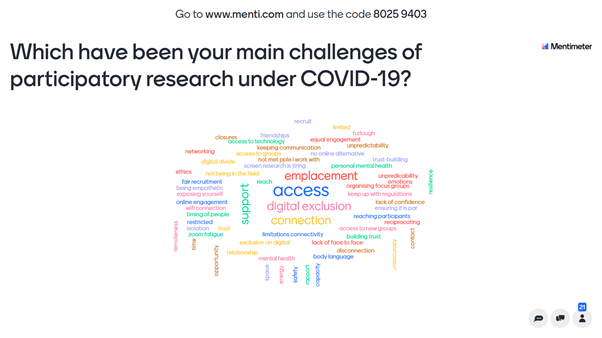

Dr Susanne Börner and Caitlin Hafferty gave presentations and facilitated discussion on digital participatory research during COVID-19. The session was also an invitation to reflect on and to re-think challenges such as accessibility, inclusion, and changing power dynamics.

Dr Susanne Börner presented her experience of conducting online participatory action research on resource scarcity and disaster risk with youth aged 12 to 18 in conditions of digital exclusion in the urban periphery of Sao Paulo. With the support from community gatekeepers and using WhatsApp as a key tool for remote research, she transformed the challenge of digital vulnerability into an opportunity for experimenting with new forms of remote participatory research. Her physical displacement from the field reinforced the importance of revisiting expectations and participant-researcher roles. It also required developing a greater flexibility and curiosity regarding research methods under COVID-19. Susanne has experimented with digital participatory tools using WhatsApp groups as the main channel of communication. Examples of activities included photography, video-making, interactive group discussions conducted through written messages and audio, as well as more practical activities such as making objects from recycled materials. Susanne reflected on the different stages of digital field research including best practices, alongside more challenging experiences in adapting to a remote research environment such as overcoming digital exclusion. Participants were also invited to question their expectations regarding participatory research during COVID-19, and to see the learning process as an important result.

Drawing on her research and experiences of digital participation with environmental and sustainability issues, Caitlin Hafferty explored the good practice use of digital tools for engaging diverse participants decision-making processes. Technology is radically changing participatory and democratic systems (sometimes called ‘e-participation’ and ‘e-governance’), raising fundamental questions about how online tools presents opportunities and issues for societies and institutions. The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated a rapid shift towards remote digital communications, bringing technology-related disparities into even clearer resolution. Digital tools can impact people’s ability to access opportunities for participation, exacerbating exclusions and digital divides. Challenges for research and governance include supporting disengaged individuals (e.g. those who lack internet access and digital skills), breaking down power hierarchies, fostering trust, and navigating privacy, security, and accountability issues. Future approaches must be carefully adapted to the context in which they are being used (and for the people who are participating), using an appropriate blend of digital and face-to-face techniques.

It is important to act with reflexivity, responsibility, and critical awareness

Bruna Montuori and Kahina Meziant presented two keynote lectures on navigating tensions in participatory research with third sector organisations. Both conducted their PhDs in collaboration with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the United Kingdom and Brazil, with a methodological and ethical emphasis on responsibility, reflexivity, and critical awareness of the researcher’s position and role.

Drawing on her volunteer and ethnographic experience with a British charity that supports forced migrants in the process of establishing roots in a new city, Kahina discussed some of the difficulties she encountered while negotiating roles in a group with diverse ideological perspectives. She offered some strategies and reflected on the value of doing a form of ethnography that is engaged and open-ended. The inductive nature of Kahina’s project enabled her to come to question the rightful subject(s) in migration studies and advocated for greater scrutiny of the workings of white, charitable structures as seen through the eyes of their users and volunteers.

Bruna gave an overview of her fieldwork in Redes da Maré, an organisation based in a compound of 16 favelas in Rio de Janeiro. She discussed her engagement with NGO members, as well as anecdotal instances in which she negotiated her role as researcher/designer, thereby supporting their long-term effort to promote social and spatial justice. One key reflection was building relationships with participants by focusing on care, and mutual trust to recognise participants’ agencies and lived experiences. While remaining attentive to issues of representation and stigmas, Bruna advocated for co-producing knowledge based on forms of reciprocity and warned against obliterating oneself in the process.

Bruna and Kahina addressed representational tensions, which are particularly visible in NGOs due to their hierarchical structures. The discussion progressed to identifying affection and emotion as productive and meaningful and identifying some approaches available that align with activist-oriented scholarship. They talked about language manoeuvring and enacting multiple identities as dimensions that inhere in conducting research and influences its outcomes.

Where are we heading?

The next frontier of participatory research must continue to build on these understandings; by doing so, we can help tackle inequalities, empower individuals, and include the voices of those are at risk of being marginalised in decision-making processes.

Now, more than ever, we need to work together as a diverse community – bringing together different knowledges in participatory research and practice to help combat global challenges and achieve a more sustainable, resilient, and equitable future for all.

Suggested further reading:

Bherer, L., Dufour, P. and Montambeault, F., 2016. The participatory democracy turn: an introduction. Journal of Civil Society;12(3): 225-230. DOI: 10.1080/17448689.2016.1216383.

Börner, S., Kraftl, P. & Giatti, L.L. 2020. Blurring the “-ism” in youth climate crisis activism: everyday agency and practices of marginalized youth in the Brazilian urban periphery. Children’s Geographies; 19(3):275-283. DOI: 10.1080/14733285.2020.1818057

Chilvers, J. and Kearnes, M. (2020) Remaking Participation in Science and Democracy, Science Technology and Human Values. doi: 10.1177/0162243919850885.

Derickson, K.D. and Routledge, P., 2015. Resourcing scholar-activism: Collaboration, transformation, and the production of knowledge. The Professional Geographer, 67(1), pp.1-7. DOI: 10.1080/00330124.2014.883958

Falco, E. and Kleinhans, R. (2018) ‘Beyond technology: Identifying local government challenges for using digital platforms for citizen engagement’, International Journal of Information Management, 40, pp. 17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.01.007.

Pain, R. and Francis, P. 2003. ‘Reflections on participatory research’, Area, 35(1), pp. 46–54. doi: 10.1111/1475-4762.00109.

Richa, N. and Geiger, S., 2007. Reflexivity and positionality in feminist fieldwork revisited. In: A. Tickell, E. Sheppard, J. Peck, T. Barnes (eds.), Politics and Practice in Economic Geography, pp.267-278.

Wynne‐Jones, S., North, P. and Routledge, P., 2015. Practising participatory geographies: potentials, problems and politics. Area, 47(3), pp.218-221. doi: 10.1111/area.12186

*Dr Susanne Börner’s research was financed by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 833401 [NEXUS-DRR].